Why cows are also good for our cities

By Dominique Cuoco

Cities get a bad reputation for being congested, impersonal, and overwhelming. This atmosphere is most noticeable on weekday mornings in New York City. There is absolutely no time to stop and smell the roses. Commuters have a common agenda: Get to work as quickly and as painlessly as possible. Of course this often involves some light aerobics and sweating profusely to catch the bus, or contorting bodies to squeeze into packed train cars. In doing so, we narrowly avoid crashing into poles, stepping on toes and getting hit by trucks.

Every now and then, we get to stop to catch our breaths and …Wait… is that …a COW?! It’s the year 2000, in midtown Manhattan. You stop to encounter a life-size, fiberglass cow staring you down, and… well, she’s beautiful.

I was a kid in NYC when my mom, a midtown commuter at the, first told me about “The Cows.” Every cow was a canvas, decorated and transformed into a piece of public art. They were everywhere – installed temporarily in public spaces all around the city. No two cows were alike, all painted to capture unique motifs – several celebrated New York’s diverse composition, others were punny, some served as canvases for impressionist art! No one knew why they were here, what purpose they served, or who allowed this to happen – but the public was both enamored and a little disturbed. Only recently did I discover the name for this event that took NYC by storm eight years ago: “CowParade.”

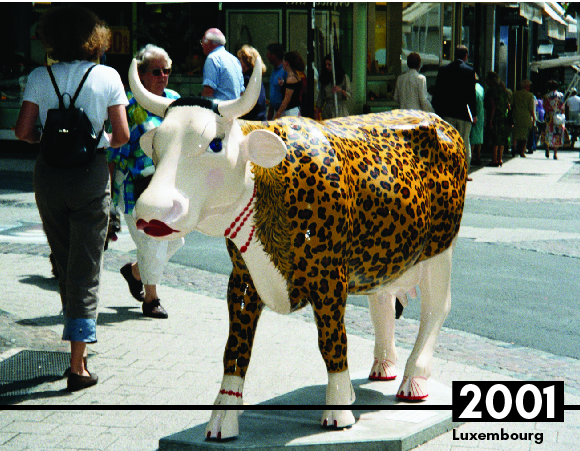

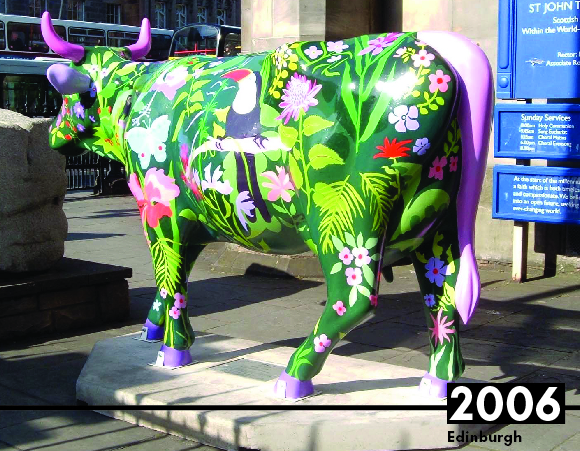

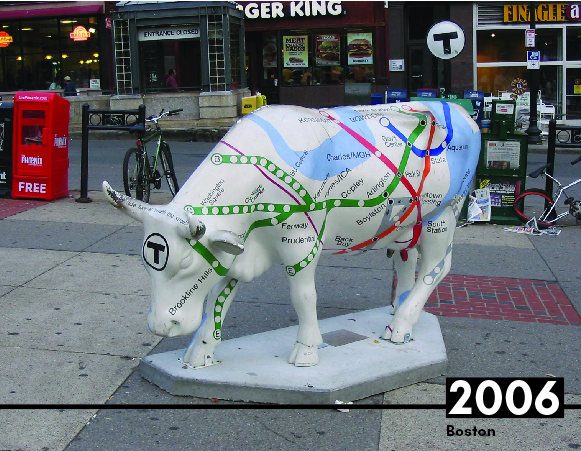

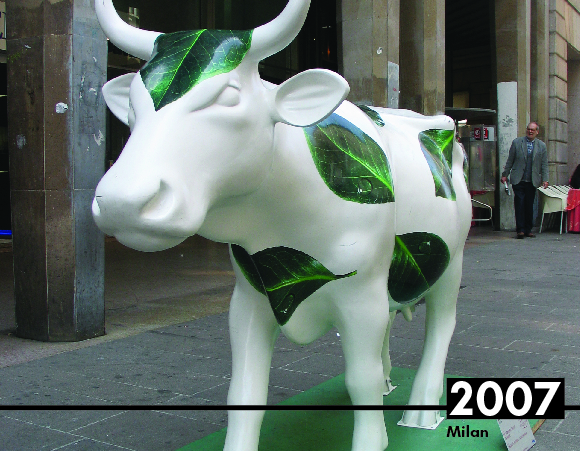

Moondrian. Photo credit: Cow Parade.

Cultural Cow Crossing. Photo credit: Cow Parade.

Cow Hide. Photo credit: Cow Parade.

CowParade Holdings Corporation launched the first “event” in 1999 Chicago, with the assistance of the Commissioner of Cultural Affairs, inspired by Zurich’s original movement in 1998. Since then, 79 global cities have held CowParade events, reaching from Wisconsin to Latvia. To date, 5,000 cows have been created by 10,000 local artists, and over 250 million people have seen at least one. Since its inception, CowParade has afforded economic and social value beyond the shock and awe of seeing something so strange and unique.

Space & Connectivity

For one, temporary public art in public and private spaces was nothing like the way it is today. There was no formal process or local government online applications. Nor was there guarantee that art would show up continuously. It was all very ad hoc, so when the cows came (by sponsorship), it was unexpected, incredibly exciting and free for all! That’s right, no accessibility issues here – if you were lucky enough to discover a cow, you had an all access pass!

When CowParade came to NYC, it was a special time in the spheres of technology and information sharing. Google was only 2 years old, and MySpace was 3 years away from invention. Community was hyperlocal and tied to physical space.

The cows brought people together, giving strangers the opportunity to react and interact in the physical realm. Everyone shared the experience of stumbling onto a cow, without smartphones getting in the way. In a New York Times article, published in 2001, a curator of special projects for Chicago’s Department of Cultural Affairs spoke about the impact of temporary art on urban spaces, and was noted saying: “Part of the attraction is artistic, and part of it is that it gives people a chance to interact with other people in a public place, which isn't that common these days. People gather around these objects and start talking to strangers. That's very important to creating a sense of community.”

Especially in the age before social media and Google, there were no digital clues or geo-locators to find the cows. Cities were actual grounds for scavenger hunts, appealing to all ages, enlisting whoever was interested. No one knew when they would disappear. And if they did disappear, no one knew what would show up next. The game was on! How many cows were there? How many could you find? Most people who took pictures of the cows got the photos printed and shared them with friends, in person. This way, there was no risk of revealing the location to the public – making the fun and playfulness of finding a new cow sustainable. That is, until the herd moved on.

The cows became a conversation piece and inspiration for years to come – directly influencing copy-cat sculptural pop up art, such as the Cincinnati pigs and the Lexington horses, and indirectly transforming urban public spaces into welcoming whimsical, temporary pieces of public art.

Economics & Health

In total, 450 cows were installed throughout New York City. The average CowParade event ranges from 75 to 150 cows. CowParade invited all artists, from amateurs to acclaimed, to submit a design and win a cow to transform. Each of the 10,000 artists were paid around $1,000, generating over 3 million dollars globally to the artist community.

Tourism revenue increased substantially as a result of the cows. In Chicago, for instance, 340 cows led to $200 million additional tourist dollars. That’s a lot of “moo-lah”!

When a CowParade event ends, they are auctioned off with live bidding. The most extravagant and costly cow, made of Crystal, was Dublin’s “Waga-Moo-Moo,” created by artist John Rocha. It sold for $146,000.

Today, CowParade has raised over $20 million dollars for charitable organizations across the world, which mostly serve children and medical institutional needs. While no other singular, temporary public art project has yet surpassed CowParade’s unprecedented impact on communities, we can see the influence carry on throughout the world in the way that cities continue to cherish public art (a bit more readily than the early millennia – thanks internet!). Next time you busy commuters are crossing streets and running up train platforms, stop and smell the roses. There may just be an amazing piece of temporary public art around the corner waiting for you!